Category Archives: Uncategorized

Reflections on Personal Sacrifice: What Lincoln did for us – and what Grant did for Lincoln

Abraham Lincoln has been apotheosized as the Savior of our land, and well he should be: He ended slavery; he put down a rebellion that would have torn our country asunder and fatally discredited the idea of representative democracy; he fought and won a free and fair election in the face of a devastating Civil War between North and South, and in the face bitter division even at the North and within his own party.

Abraham Lincoln has been apotheosized as the Savior of our land, and well he should be: He ended slavery; he put down a rebellion that would have torn our country asunder and fatally discredited the idea of representative democracy; he fought and won a free and fair election in the face of a devastating Civil War between North and South, and in the face bitter division even at the North and within his own party.

Lincoln was, without doubt, the greatest leader our Country has ever produced, and one of the greatest leaders that any country has ever produced. But no one accomplishes anything on the scale of what Lincoln did unaided, and he was no exception. Lincoln was the senior member of one of the most remarkable partnerships in human history: Lincoln & Grant.

Grant was the junior partner, but no less essential of the two. Without Lincoln Grant would never have risen from obscurity to lead the Armies of this great Republic to victory. Without Grant’s military prowess, Lincoln would never have accomplished his political achievements – Emancipation, the 13th Amendment, Reunification.

Lincoln was the leader, but Grant was his essential partner, sword, and hammer.

Grant did much more for Lincoln than win his military battles. First, Grant secured Lincoln’s legacy. Andrew Johnson might well have destroyed all Lincoln accomplished had Grant not been at hand to act as a curb and a check on a President that even considered attempting an executive coup. Second, Grant expanded on Lincoln’s legacy during his own Presidency, fighting hard for the rights of the Freedmen as long as an electorate weary nearly to death of struggle and strife would let him, and making a lasting peace with Britain that formed the basis of the Special Relationship that stands to this very day.

But that is not nearly all that Grant did for Lincoln.

Lincoln is renowned as our greatest President, while Grant is regularly derided as among our worst. But the reality is that he was not among our worst Presidents – not by a long shot. Grant was a remarkable President, both for what he actually accomplished, and for what he tried to do.

During Grant’s Presidency and after, he was viciously criticized as a stupid, alcoholic, corrupt, and foolish bumpkin. Lincoln endured similar vicious attacks during his Presidency. But there is one huge, inescapable difference between the circumstances of Grant and Lincoln: Lincoln died.

Lincoln was murdered, and martyred. And freed from the vicious slings and arrows of his opponents. Had Lincoln lived, and served out his second term, the savage attacks directed at Grant would have been directed at him. Lincoln’s reputation would have been savaged and torn by those bitterly unable to accept the defeat of the Confederacy, as was Grant’s.

But Lincoln died. Grant stepped in, picked up Lincoln’s standard, and carried on the fight – and drew fire. In succeeding Lincoln as President, and as the standard bearer of the Union, and Liberty, and Equality, Grant became the target of the hate and enmity of those who hated the Union and loved slavery, of those who led the Southern states into a futile and devastating war for a doomed institution, and of men who never saw a battle, military or political, who could attack Grant after his death from the safe refuge of their Ivy League ivory towers. They could not accept their own folly, so in the years after the War, and even more in the years after Grant’s death, they systematically attacked, chipped at, wore down and eviscerated Grant’s reputation, to the point where now one of the greatest leaders of this great Republic, one the greatest leaders of any nation, and one of the most practical promoters of liberty and equality in human history, is denigrated and cast down by the people whose very liberty and prosperity is his legacy.

Had Lincoln lived, they would have done this to him. But Lincoln died for us, and Grant took up his standard. Lincoln sacrificed his life for America. Grant sacrificed his reputation for Lincoln.

Grant performed five great services to our great land: He defeated the Confederate armies on the field of battle; he defeated Andrew Johnson at the ballot box; he ushered in an era of peace  abroad and at home; he fought for the rights of the Freedmen and of Native Americans; and he took upon his own back the blows that would have fallen on Lincoln’s, saving Lincoln to be for us, the symbol and the example we need him to be.

abroad and at home; he fought for the rights of the Freedmen and of Native Americans; and he took upon his own back the blows that would have fallen on Lincoln’s, saving Lincoln to be for us, the symbol and the example we need him to be.

“Blessed are ye, when men shall revile you, and persecute you, and shall say all manner of evil against you falsely, for my sake. Rejoice, and be exceeding glad: for great is your reward in heaven: for so persecuted they the prophets which were before you.”*

Just so. Great will be your rewards in heaven, Lys.

*Matthew 5:11 & 12.

The Black Flag of Abd al-Karim Qasim

I developed an affinity for Iraq during my service there. I find myself particularly drawn to the period of the Monarchy, moved as I am by the pathos of the murdered King, struck down in his youth, along with his family the by the henchmen of the brutish General Abd al-Karim Qasim in 1958.

My sympathy for the King has moved me to collect a few small relics of the Monarchy period: Military insignia, old photos from wire service archives, and the jewels of the collection, my two British SMLE MKIII* Enfield rifles, made in 1918 and 1935, marked with the Jeem of the Iraqi Army.

The latest addition to my collection is the flag pictured with this article, a vintage example of Qasim’s 1958 flag. I hesitated to purchase it, because of the antipathy I feel for the man who governed under it, and for his regime, and for the catastrophe it ultimately proved to be.

Qasim sowed the wind, and he reaped the whirlwind on February 9th, 1963 when he himself was overthrown by a military coup and killed, ignominiously dumped into an unmarked grave. Qasim and his flag shared a remarkably similar fate. Qasim disappeared after his murder. The location of his grave was unmarked and quickly forgotten. From the day of his death until his body’s discovery in 2004, neither any monument to Qasim nor fragment of his remains were known to exist. The only testament to his life and misrule were the wire service photos and written records that documented his regime.

Qasim’s flag shared a remarkably similar fate. Nearly every flag ever flown over Iraq still exists, is still made, and can still be purchased brand-new. A quick internet search produces brand-new copies of Iraq’s national flag and royal standard of the Monarchy; the Ba’athist 1963 flag; Saddam Hussein’s 1991 flag; the interim 2004 flag; and Iraq’s current flag, adopted in 2008. When I was in Iraq in 2006 and 2007 I acquired copies of both the 1963 flag and the 2004 flag.

But Qasim’s flag is practically extinct. Until I stumbled across the example in my collection, I had never seen a physical example of Qasim’s flag, old or new. It was as if it disappeared into his grave with him.

Ultimately, this is why I broke my rule and bought this relic from Qasim’s regime. It is an extremely rare historical artifact, worthy of conservation, even if not honor.

CV

Manning Reserve Component Units for Mobilization

Fruits of the Revolution

Our Ambivalent Iraqi-Kurdistan Policy

Nothing New Under the Sun

I’ve been reading Great Expectations by Charles Dickens. This book originally appeared in serial form in 1860, and in book form in 1861. Yet this morning, I came across an observation as trenchant and penetrating in today as it was the day Dickens published it a century and a half ago.

I’ve been reading Great Expectations by Charles Dickens. This book originally appeared in serial form in 1860, and in book form in 1861. Yet this morning, I came across an observation as trenchant and penetrating in today as it was the day Dickens published it a century and a half ago.

In it, the main character and narrator, Pip, an apprentice bound to his uncle Joe, returns home late one evening to find that his abusive, borderline personality disordered sister has been badly injured by an attacker.

Pip observes and comments upon the ensuing criminal investigation:

“The Constables, and the Bow Street men from London — for this happened in the days of the extinct red waistcoated police — were about the house for a week or two, and did pretty much what I have heard and read of like authorities doing in other cases. They took up several obviously wrong people, and they ran their heads very hard against wrong ideas, and persisted in trying to fit the circumstances to the ideas, instead of trying to extract ideas from the circumstances … It was characteristic of the police people that they had all more or less suspected poor Joe (though he never knew it) …”

There can be no doubt that police today are infinitely more competent, diligent, honest, and effective than these early lawmen lampooned by Dickens. There can also be no doubt that in the great majority of cases, police and prosecutors are motivated by nothing more than the sincere desire to get the right man – and that, in the great bulk of cases, they do get the right man.

But the sad fact remains – and, given the nature of poor, flawed, fallen man, likely always will remain – that some innocent men are accused. And tragically, some of these wrongly accused, are convicted.

It is my firm belief that, in those few tragic cases when the innocent are falsely accused and convicted, the cause of the injustice can be traced back to the same cause that Dickens cast light upon more than 150 years ago: The police who made the cases against these people, and the prosecutors who brought the charges, “persisted in trying to fit the circumstances to the ideas, instead of trying to extract ideas from the circumstances”, as Dickens observed so long ago.

There are many ideas out there as to how to avoid wrongful convictions – one of which being training police on how to more effectively interrogate suspects, so as to elicit truthful statements rather than mere to extract confessions. But most of all, Dickens’ clever observations bring to mind another important idea: That in this country, the accused is presumed innocent, until proven guilty, no matter how strongly we might suspect otherwise; that the prosecution must be forced to prove each and every element of every charge brought, in order to secure a conviction thereon; and that each and every procedural and substantive Constitutional right must be scrupulously honored throughout the investigation and trial.

I suspect that many people misunderstand, in a fundamental way, just exactly why we follow these constraints. We don’t do so, as some seem to believe, out of any sense of fair play or solicitude toward guilty men: we do them “lest while [we] gather up the tares, [we] also uproot the wheat with them.” We do these things for the same reasons that we prosecute criminals: We do them to protect the innocent.

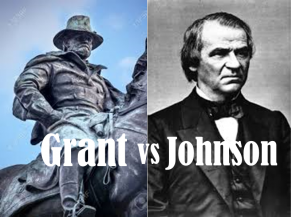

Grant vs. Johnson: Constitutional Smack Down

I watched the first episode of Kiefer Sutherland’s new show Designated Survivor tonight. Aside from the inevitable bits of gratuitous sanctimony spouted by President Tom Kirkman (Kiefer’s character), the show was pretty good. What I found most interesting, however, was the teaser trailer of scenes from next week’s episode, where we see General Harris Cochrane (played by Kevin McNally) sounding out Presidential aide Aaron Shore (Adan Canto) about what would amount to a coup d’état to replace the accidental President Kirkman, after devastating attack on the U.S. Capitol during the State of the Union address kills the incumbent president, the entire cabinet (save “designated survivor” Kirkman), the entire Congress, the whole Supreme Court, etc., leaving Secretary of Housing and Urban Development Kirkman to ascend to the Presidency by default.

I watched the first episode of Kiefer Sutherland’s new show Designated Survivor tonight. Aside from the inevitable bits of gratuitous sanctimony spouted by President Tom Kirkman (Kiefer’s character), the show was pretty good. What I found most interesting, however, was the teaser trailer of scenes from next week’s episode, where we see General Harris Cochrane (played by Kevin McNally) sounding out Presidential aide Aaron Shore (Adan Canto) about what would amount to a coup d’état to replace the accidental President Kirkman, after devastating attack on the U.S. Capitol during the State of the Union address kills the incumbent president, the entire cabinet (save “designated survivor” Kirkman), the entire Congress, the whole Supreme Court, etc., leaving Secretary of Housing and Urban Development Kirkman to ascend to the Presidency by default.

This depiction of an American General as a boorish brute brooding over and plotting against the supposedly feckless, inexperienced President was noteworthy in two respects. First, because of the utter inevitability that a lazy bunch of Hollywood screenwriters hacking away at one of the formerly “big” three networks would trot out this tired, predictable, hackneyed old trope rather than construct a fresh and interesting plot line for their show. The patriotic egotist in uniform plotting to seize power out of a misguided sense of patriotism was an interesting figure when portrayed by Burt Lancaster in Seven Days in May, and was disturbingly compelling as Brigadier General Jack D. Ripper in Dr. Strangelove. But in General Harris Cochrane, it’s just tiresome. Alas, Jack Bauer is a lot more interesting than Tom Kirkman.

Hollywood’s kneejerk impulse to reach for a General as its utility bogeyman is also noteworthy because of just how counterfactual and a-historical it really is. In fact, to the limited extent that Generals have been involved in episodes threatening the Constitutional order in America, they have acted as a bulwark of safety for civil government, and not as an instrument of bludgeon against it. I discussed one such incident ten years ago when I published “Soldiers in the Public Square: The Legacy of the Newburg Conspiracy” in Military Review. That piece examined General George Washington’s role in suppressing mutinous tendencies (albeit over legitimate grievances) among officers of the Continental Army. Today, however, I am interested in another General facing another challenge: Ulysses S. Grant in Reconstruction America.

1866 inaugurated a tumultuous period in American politics. Following Abraham Lincoln’s assassination in 1865, Vice President Andrew Johnson ascended to the Presidency. Lincoln selected Johnson as his second term running mate for reasons of strategy and expediency: By selecting Johnson, a war Democrat, Republican Lincoln could reach across party lines to siphon away Democrat voters from their party’s nominee, George B. McClellan. Additionally, Johnson was a Unionist southerner hailing from Tennessee. Although a rebel Confederate state, Tennessee had been bitterly divided over the question of secession and still harbored a strong pro-Union minority, to whom Johnson could appeal.

Tragically, Johnson’s Unionist sentiment was about the only thing he had in common with Abraham Lincoln. Lincoln had pushed hard for the 13th Amendment to abolish slavery, and over the course of the war had moved gradually but consistently in the direction of greater social and political rights for blacks generally and for freed slaves in particular. In fact, when President Lincoln gave a speech near the end of his life calling for the franchise to be granted selected Freedmen, such those who had served in the Union Army, he was overheard by one John Wilkes Booth. Outraged, Booth resolved that this would be the last speech Lincoln ever made. Booth made good on the threat, murdering Lincoln a short time later.

Unfortunately, Andrew Johnson was a vicious racist who had no truck with Lincoln’s vision of political equality regardless of race. Where Lincoln continually moved further and further in the direction of social and political equality for blacks, Johnson envisioned a post-war world where the Freedman would amount to little more than serfs under the control the white majority, with the only improvement from their former status being that they would not be deemed chattel as they previously had been.

Johnson’s virulent racism put him on a collision course with the Republican controlled Congress. Congress, controlled by the Republican’s “radical” faction, desired an aggressive Reconstruction policy that would push for what amounted to a social and political revolution in the areas of civil rights, political rights, and racial equality. Johnson would have none of it, vigorously resisting the Republican policy and pursuing his own policy of restoration of the Southern states to the secessionist whites who had dominated them before the war.

With such diametrically opposed visions, conflict was inevitable. By mid-1866, tensions between President Johnson and Congress were riding high. Republican leaders in Congress began to fear that Johnson and supporters would resort “to the use of force against Congress, a prospect that became ‘rather common talk.’”[1] Massachusetts Senator Charles Sumner “feared that the President was planning a coup d’état, which would mean ‘revolution and another civil war.’”[2] Rumors circulated that Johnson wanted to replace Congress, and that he had asked his Attorney General whether a Congress composed of Northern Democrats and Southern Congressman could supplant the elected Republican Congress.[3]

General Ulysses S. Grant, then in command of the United States Army, was aware of these swirling rumors. He obviously gave them credence, writing to General Philip Sheridan, who was commanding occupation troops in the South, that “we are rapidly approaching the point where he [Johnson] will want to declare [Congress] itself illegal, unconstitutional, and revolutionary.”[4] Given the great popularity and prestige that Grant enjoyed as the victor of the Civil War, and given Grant’s position as head of the Army, Johnson could hardly proceed with such a scheme without Grant’s support. And he appears to have sounded Grant out about it. “Rumors of this alarming conversation spread like wildfire.”[5] Although the exact content of neither Johnson’s trial balloon nor Grant’s response can ever be ascertained for certain, one thing is clear: General Grant left President Johnson in no doubt that the Army would disperse any usurper Congress that Johnson might try to set up, and would sustain the true and lawful Congress that Johnson so hated.

Those who know me well know that I revere Ulysses S. Grant and cherish his memory. Unlike most people, who appreciate Grant’s contribution as the sword in Lincoln’s hand during the Civil War, I love him not only for that, but also for his truly great contributions after the War. Grant’s Presidential administration has long been derided for alleged corruption – none attributable to Grant himself, even by his detractors. But what has long been overlooked – tragically, in my view – are Grant’s vigorous efforts on behalf of the Freedmen of the former Confederate States, and his heroic role in smashing out of existence the first incarnation of the Ku Klux Klan during the same period. One can fairly say that U.S. Grant was Commander-in-Chief of America’s first war on terror – a war he made sure the terrorists lost.

Happily, a new generation of historians has begun to show a new appreciation for Grant’s fight for liberty during the post-war years. But I believe that the shadowy, obscure episode I describe above deserves a place in the pantheon of his other mighty deeds. By standing up to President Johnson’s machinations for a compliant Congress that would do his will, Grant not only kept Lincoln’s legacy alive in the short term, but also breathed new life into the bedrock principal of American Constitutional government: the division of power among separate, coequal branches of government.

Finally, it is worth noting that Grant did not just protect Congress against the grasping of the President. He protected the Presidency, too. As is well known, Andrew Johnson enjoys the dubious distinction of having been the first President to be impeached, over his defiance of Congress over the Tenure in Office Act. Whatever the merits of their case, the Radical Republican Congress was well within its rights to impeach Johnson (which, in the event, resulted in Johnson’s acquittal by the Senate). Where Congress tried to exceed its authority, however, was in their attempt to strip Johnson of his Presidential powers before conviction. Thaddeus Stevens, a leader of the Radical Republicans, introduced legislation that would have suspended Johnson from office pending the outcome of his impeachment trial.[6] “Determined to resist,” Johnson sought out Grant to determine where he (and the Army) stood.[7] Despite the fact that Grant “had come to detest Johnson … his duty was clear” – he and the Army would resist any effort to strip the President of his authority prior to conviction at an impeachment trial. Without Grant’s support, Stevens’ plan was futile, and was eventually dropped.[8]

[1] See Impeached: The Trial of Andrew Johnson and the Fight for Lincoln’s Legacy, 2010, by David O. Stewart, page 70.

[2] Ibid, pages 69 – 70.

[3] Ibid, 70.

[4] Ibid.

[5] Ibid.

[6] Jean Edward Smith, Grant, 2001, page 444.

[7] Ibid.

[8] Ibid.

July 14th, 1958: Day of Infamy

An old rifle reposes in a safe at my home – an SMLE No. 1 Mark III*, made in Britain by Birmingham Small Arms in 1936. It is very well-worn; the stock is patched and cracked; it has at least one mismatched serial number. It is not a particularly good or noteworthy example of the type, except in one respect: This rifle bears the Arabic letter jiim – the property mark of the Iraqi Army. It is an artifact of another age, a time before the nightmare of terrorism and war, chemical weapons and genocide, before Saddam Hussein and Abu Bakr al-Baghdadi; it is itself a relic of a troubled and tumultuous time to be sure, but a time that by today’s awful standards would almost seem idyllic by comparison, a time when Iraq had some dignity and some hope for the future under the King. But this rifle also represents something else – something dark and tragic and foreboding, because it was in the hands of the men that, in a fundamental sense, set in train the tragic chain of events that brought Iraq to where it is today.

Many events and influences brought Iraq to its current tragic state: George W. Bush’s decision to invade the country in 2003; Barack Obama’s decision to prematurely pull out of Iraq; Saddam Hussein’s rash decision to invade Kuwait in 1990; his arrogant game of cat-and-mouse with the international community over weapons of mass destruction afterward; and a hundred other causes. But in my opinion, the real proximate cause of Iraq’s troubles; the single, indispensable event without which Iraq’s hideous mutilation of today would never have occurred, is the coup d’état masterminded by Iraqi Army Brigadier General Abd al-Karim Qasim on July 14th, 1958 – the so-called “Revolution” where the Iraqi Army murdered its King and his family and placed a General on the throne.

The Iraqi Army had been active in politics before the 1958 coup. In late October 1936, Iraqi Army General Bakr Sidiqi, having been entrusted as acting Chief of Staff during the absence of his superior, led a putsch against the government of Prime Minister Yasin al-Hashimi; Sidiqi himself was assassinated and overthrown in a 1937 coup of the Seven, led by Colonel Salah al-din al Sabbagh; this was followed by coup of the Four Colonels, better known as the Golden Square, in February 1940. These same officers instigated yet another coup – the “Rashid Ali coup,” in April 1941.

These coups, however, were fundamentally different than the ersatz “revolution” that brought Qasim to power. For in these earlier military interventions, the Army worked within the Constitutional framework ratified by the Constituent Assembly that convened in 1924, and which had remained in place upon Iraqi independence in 1932. When the Army moved during this period, it moved to change policy; to push aside disfavored leaders; and even went so far as to force a change of Regents. But the Army never moved against the King, and never sought to tear down the entire edifice of the state.

All that changed on July 14th, 1958. Shortly before that time the Iraqi government had ordered troops to move west to bolster the position of King Hussein of Jordan. These troops would pass by Baghdad en route. Qasim saw his chance, executing a well-planned move to seize power. Unlike the masters of earlier coups, Qasim didn’t just strike to push out a Prime Minister or change government policy – he struck at the monarchy itself, and in so doing he changed the course of Iraqi history for the worse.

In Iraq’s Armed Forces: An Analytical History, Ibrahim Al-Marshi and Sammy Salama describe the Iraqi Army as existed prior to the 1958 as a “moderator” Army that exercised a restraining power over Iraq’s civilian government. But if the Iraqi Army acted as a moderating force on Iraq’s civilian cabinets, then the Monarchy moderated the Army, with the King serving as an organic curb on the Army’s worst impulses. Among the first acts of the “Revolution” was to give in to those impulses. Shortly after 7:00 AM the rebel force sent to secure the King’s residence at the Rihab Palace entered the grounds after the palace guards had been ordered to cease fire. The insurgent forces sent an emissary into the palace to summon the royal party into the courtyard, where they were summarily shot down by one Captain Sab’ – the King; the Crown Prince and his mother, the widow of King Ali of Hejaz; the King’s aunt; and a number of Pakistani servants. The King was only 23 years old at his death.

That Qasim and his cronies had some consciousness of guilt is betrayed by the fact that Qasim later denied having ordered the King’s death and tried to blame his lieutenant in the coup, Abdul Salam Arif; by stories circulated that Captain Sab’ or another soldier had gone rogue and killed the royal party on his own initiative; by claims that the wounded King was transported to a hospital and died there. But deeds speak louder than later words: the malice at the heart of the revolution was laid bare by the fates of both Crown Prince Abd al-Ilah and Prime Minister Nuri al-Said, both of whose corpses were savagely and publicly mutilated after their murders.

The murder of the King removed all restraint from those who would seek power in Iraq ever after. It planted in their hearts the seed of rapacity and of heartless cruelty. It legitimized, in their minds, the murder of those who stood in their way. But most devastatingly, it planted in their hearts the cold fear of being killed and overthrown just as they themselves had killed and overthrown their predecessors. Like the “Presidential grub” alluded to by Abraham Lincoln, this fear gnawed away inside the heart of the body politic corrupting and it and rendering it savage. The process culminated in the brutal heart of Saddam Hussein, a genius in the art of oppression who held Iraq fast in his hands through brute terror, vulgar public display, and a cynical manipulation of the institutions of the state to penetrate into the deepest recessions of public life.

Ironically, among the innumerable victims of the military and Ba’athist regimes that ruled Iraq from 1958 until 2003, none suffered worse than the Army itself. Unlike his predecessors, however, Saddam Hussein was determined never to fall victim to a coup himself. To avoid this, he emasculated and thoroughly cowed the Iraqi Army. He wasted its strength on futile wars against the Kurds and the Iranians; he sacrificed the flower of the Army to his hubris in the invasion of Kuwait; and he goaded and provoked the international community to the point that the United States vaporized the Iraqi Army in 2003.

With his coup in 1958, Qasim sowed the wind. He reaped the whirlwind when he himself was overthrown, and then executed and buried in an unmarked grave, on February 8th, 1963, with his remains to be rediscovered only in 2004. But he did not reap the whirlwind alone. Ironically, the instrument that brought and sustained him in power, and that ultimately destroyed him, itself suffered much at the hands of Qasim’s successors.

Can we say that the Army did not deserve its fate? The Iraqi Army made itself the instrument of the brutal and crass. As such, it was an Army unworthy of its people: It was an Army that murdered its King.